Two Worlds Apart

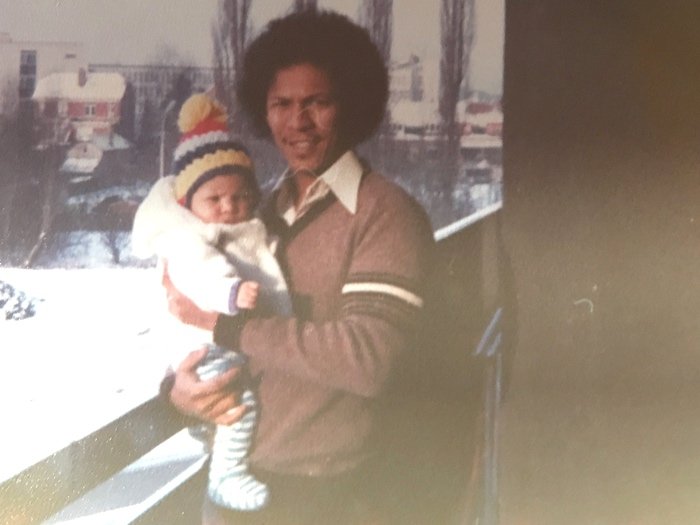

Here is a picture of me. And below is a picture of my dad and me as a baby. My dad comes from Melaka, Malaysia. He’s a member of a community of Portuguese-speaking Eurasians and Hokkien Chinese. In the picture, he’s adapting to the cold winter in Belgium, his first snowy winter ever.

My dad was an economic migrant who came to Belgium looking for better prospects. In his twenties, he hitchhiked to Europe and ended up in Belgium, where he met my mother in a center for undocumented migrants. She was there to meet a friend, who did not show up that day. But my father was there, with his guitar, looking remarkably like Jimi Hendrix. She fell for him instantly.

My mother came from a wealthier background. My grandfather was a general major in the Belgian army. He had an extensive library of books on warfare, especially World War II tactics, that I would read during vacations. My grandparents did not consent to my mother’s marriage to what they called “an adventurer.” They worried what would happen to their mixed-race children. My dad vowed to always support his family and work hard to keep us fed and alive. Without a high school diploma his best option was to train as a bricklayer. Thus, I was born in Belgium in a solidly working-class family, and my sister was born six years later. My mother was a homemaker. We scraped by on one income with an ancient car and hand-me-down clothes that I was relentlessly bullied for. But, due to generational luck, my parents were able to buy a run-down house with an outdoor outhouse and no central heating, which my father (being a builder and carpenter) slowly renovated over the years.

As a child, I developed nerdy interests and did well at school, which delighted my parents. But we weren’t a bookish family. I found the town’s library when I was nine and went there after school. I was fascinated by the Italian Renaissance, notably Leonardo da Vinci. I loved his drawings, especially of fantastical contraptions, and his mirror handwriting. The notion of the universal man appealed immensely to me, influencing my continued thirst to dabble into various pursuits. With the money I got for my first job and my family all pulling together, I bought a Renaissance lute at the age of 17. I traveled to Florence by train to see the great Italian Renaissance masters. I read my first philosophy books in my teens: Castiglione’s Courtier, Machiavelli’s Prince, and Pico’s Oration on the Dignity of Man.

At school, I had some very close friends, who, like me, were socially marginalized. One friend had goats at home and lived very sparsely. Another had parents who worked in the local factory. I was one of three people of color in my primary and secondary school. As a result, if, say, my classmate copied my work surreptitiously, teachers always assumed it was me. At age ten, during summer camp, there was someone who stole things, and the camp leaders believed it was me. I refused to confess and spent about two weeks in solitary confinement. Out of sheer racism (it was not my grades) many of my teachers tried to railroad my future into vocational work, which in Belgium at that time happened already at age 12. Fortunately, my mother, having been born in a middle-class environment herself, realized that studying was important, and she resisted the teachers’ advice. And so, I was sent to “general” rather than “vocational” education.

College went very smoothly, and after college came the idea of graduate school. It took several attempts to secure funding for my first PhD in art sciences and archaeology. I did not know how to network. During my academic career, which took some difficulty getting started (I did a second PhD in Philosophy, which I came to love more than anything else, and I had multiple postdocs), I had to learn the game of fitting into a middle-class context. Suddenly, being a person of color was cool and not something that licensed people to attack you out of nowhere or assume you were guilty of whatever it was. I learned how to eat properly in a restaurant and act with basic decorum. Yet, I found out that among white progressive academics in Belgium, the UK, the Netherlands, and the US, there are still subtle ways where exclusionary tactics are played out.

For a long time, I believed that I was in a very disadvantageous position because of my background. How could I properly emulate this middle-class life? But lately, being working-class and a mixed-race person has given me some advantages. Particularly, I do care what people think of me, but I balance that with other sources of knowledge, and I try to find sources of affirmation and values outside of what others think.

I like Audre Lorde’s idea of survival (which she contrasts with safety, getting a proper job etc), a rich notion of finding sources of value within the self and expressing and fully realizing the self. I think focusing on purely economic circumstances in policy is a huge mistake. Being working class and frequently finding it challenging to reach the end of the month when I grew up, self-realization in the full sense still mattered to us. Indeed, my entire philosophical project is focused on the excesses. I try to explain (for instance, in my forthcoming book Wonderstruck) why humans, even when they are in quite difficult material circumstances, still create art and music, engage in costly religious festivals, and delight in philosophical reflection.

I see a growing awareness of issues of class and labor conditions in academia. As our collective circumstances erode, this is becoming a pressing issue. Many tenured academics (like me) find themselves in the difficult position of witnessing this and only being able to make small, if any, changes to structural injustice. This is a source of tremendous frustration, which I believe gives rise to many culture war and other problems in academia. As Liam Bright points out aptly, when it’s impossible to change structurally, people resort to white psychodrama, quibbles and infighting that is not going to end racism, elite capture, or growing inequality. Yet, we must find a way. Growing up working-class, I know we are resourceful and compassionate, that we do not only seek connection to find gain but also to genuinely find friendship and solidarity. We mustn’t give up trying to improve conditions for all, especially for contingent faculty and grad students.

Helen De Cruz is the Danforth Chair in the Humanities at Saint Louis University.